A Christian Essay in Aesthetic Value

" No, That's not art its, that's just telly, made with telly values"

Measuring by the criterion of self-communication we may distinguish

between a ‘genuine art form’, and that which merely resembles the arts but is,

in fact, simple craftsmanship or some kind of entertainment or source of

information in which the maker gives nothing of himself or herself and only

some trivial aspect of the subject is depicted. We may judge the intention to

communicate as to its depth and breadth, and may affirm the validity of

considering art forms superior or inferior in quality by reference to the scope

they afford for self-communication. When we do judge in this way we find a new

basis for saying that the traditional scale of values in such matters holds

good, albeit with certain nuances favourable to the use of modern forms and

techniques in the established arts. The distinction between art and art-like

activity is understood instinctively both by artist and audience. Grayson Perry

says “No, that’s not art, that’s just telly, made with telly values” with

respect to his own television series, and we know what he means, as we know the

difference between an artist’s work and an artisan’s. – Mr. Perry does not say of his programmes

‘this is the best of me’, but ‘this might be of interest’. The act or work of

the artist is endowed with a meaning from the depths of the soul which appeals

to the audience at the same level; we know by instinct that “when Art is too

precise in every part”, when it is entirely the product of the conscious mind,

is over-deliberate or didactic in its intentions, is a confection of

superficialities, witticisms and wordplay, it is an inferior work. We know too

what ‘cheap music’ is, it is that which a composer purchases at less than the

cost of his or her entire being; its potency lies in that, at its best, while

its breadth is limited to a single definite subject or theme, its depth need

not be less than that of serious music, and the lack of context or consequence

inherent in the form might even sharpen its effect, as with the exquisite

misery of Ma Rainey or the unbridled joy of Jelly Roll Morton and Bix

Beiderbecke. At its worst, however, cheap popular music bears no relation to

any artistic concept on the part of its writers, they merely ‘sup the beer of

them that throw the darts’, describing parasitically the experience of others.

St. John Paul II reminds us that every artistic work or act is a failure in so

far as that it is impossible for any human artist to realise his or her

artistic concept: “All artists experience the unbridgeable gap which lies

between the work of their hands, however successful it may be, and the dazzling

perfection of the beauty glimpsed in the ardour of the creative moment”. We may, however, judge the extent to which

the artistic act or work succeeds or fails in its realisation of the concept in

any particular case. It is here that technical expertise or the lack of it,

enters the frame. Although the authentic artistic concept is generated at the

subconscious level, its formulation and realisation are intellectual activities

requiring the greatest deliberation and application. We may judge whether the

skill and effort applied to the task have proven sufficient.

|

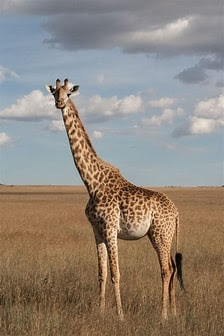

| Now that's art! - made with Grayson Perry values |

There is an apparent tension between the first criterion and the second, namely that the work or act may be judged in terms of a communication concerning a certain subject. We may understand Walter Pater’s dictum that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” to mean that music’s ability to communicate without use of the intellectual faculties mediated by language render it supreme amongst the arts, although we should bear in mind the advances in non-figurative and semi-figurative work in the visual arts since he wrote in the 1870s. This reinforces the appearance of a tension, seeming to privilege the self-communication of the artist over any relationship between him or her and any subject beyond the artist’s own interior landscape as the lack of visual depiction may be mistaken for a lack of representation. In fact, however, because the artist deals with the ‘inmost reality’ of the subject, which is to say the truth concerning it, precisely as it is reflected within the deepest reaches of his or her own soul, there is no tension at all between either self-communication and communication upon some other subject, or else between representation in an explicit and in a non-figurative manner. It is not only the poet, like St. Caedmon of Whitby, who ‘sings creation’; from the caves of Lascaux to the works of Damien Hirst the visual arts have presented the audience with creatures not in themselves as they live in the wild – that is the business of the zoologist – nor as the intellect fancies they might be, but as they truly are at the essential level, not precisely as God sees them, but as the divine idea from which they are formed is reflected in the divine image in which the artist is made; at this level it is an irrelevance whether the subject is presented pictorially, verbally, musically or by some other form of art. A good deal of work that gives the appearance of being non-figurative in fact abstracts from natural forms; the transition to the abstract is, perhaps, best illustrated by futurist works such as Balla’s series of swallow paintings in which geometric forms grow from the birds’ flight. Robert Motherwell’s comments are apposite: “Abstract art is stripped bare of other things in order to intensify it, its rhythm, spatial intervals and colour structure. Abstraction is a process of emphasis, and emphasis vivifies life”. What matters is the extent to which the work succeeds in the act of communication; we may judge whether we know more of the subject for having encountered the work, not just in itself but in its relations – physical, psychological, spiritual and cultural – with others, with the artist, and with God – have we grown in our understanding of and love for the subject? When the subject is an artefact it is these relations that are the truth we seek to understand, them and the substances from which they were fashioned as it is in the material of the artefact that the work of humanity meets the work of God. An artefact has what might be called human relations and also socio-economic relations, and its meaning for the artist and society is derived from those relations such that we cannot know, say, a chair without understanding them. The item was made by an amateur, an artist or a factory; it was bought, given, found, inherited or stolen; and it plays a particular role in the life of the household. The task of the artist in addressing such a subject, indeed to address any subject at all, is to make manifest that which is not readily apparent about it, or which its mundanity causes us to overlook. We may judge whether the technique employed assists in that process. The simple act of presenting a subject in a place of artistic encounter may be sufficient to manifest aspects of the inner reality that generally go unremarked; but the absence of consent to, or expectation of, an encounter will ordinarily negate the artistic intention of such a presentation. The use of media and techniques limiting themselves largely to the surface appearances of subjects is seldom effective in conveying very much truth, except in cases where, whatever the ostensible subject, the work is actually addressed to the subject of superficiality itself – a central concern of pop art. I have said very little about television, and do not intend to say very much more, but I would question the ability of a medium apparently addicted to a realism that is unreal, and a naturalism owing little to nature, to move far beyond the surface appearance of things because, whilst only some works are abstract in form, all successful art abstracts essential truth from visible or sensible phenomena, and the medium seems to allow little scope for such an abstraction.