The Past Isn’t Even Past

A fond farewell to Catholic Truth and its Catholic Truth

(Scotland) blog after twenty-four years fighting for the Faith; it will be

sorely missed. “Ae farewell and then for ever.”

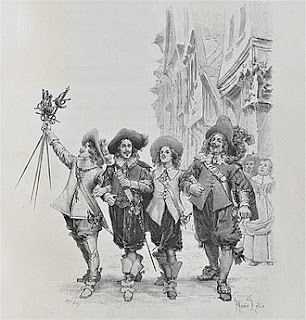

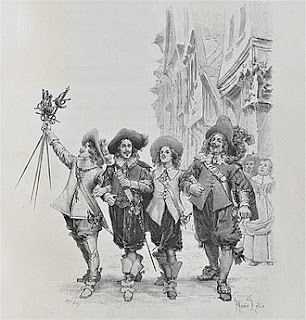

The

newsletter once published a letter in which I replied to a priest who had said

he could never make any sense out of why The Three Musketeers had been on the

Index of Prohibited Books. We learn what

we learn in the course of our formal education – and even that in itself is

subject to the vagaries of an individual’s schooling – then we forget much of

it if not quite all. What might remain

to us is a general impression that can serve as a broad foundation for our future

prejudices; but in many cases we do not retain even that, and the entirety of

our attitude to any particular subject will be formed on the basis of our

cultural environment, which is to say our media environment.

Having

mentioned historical fiction we must give it some further consideration because

it is necessarily the most vivid and engaging material that sticks in the

memory and shapes our understanding of history, and that will very often be

fiction whether written or broadcast.

Who controls the past controls the present: who controls the present

controls the future because the past isn’t really even past as our

interpretation of history underpins our social, political and cultural

attitudes. Indeed, much of our political

development in the nineteenth century may be traced to the embrace by

conservatives under the n--- D--- of the Catholic alternative to the Whig

interpretation of history understood as a Tory version. We are who we are

because we think we were who we think we were, and that includes being a ‘we’

in the first place as well as what ‘we’ might think of ‘them’ whoever ‘they’

might be.

Returning to

my example, The Three Musketeers is a work the contents of which are generally

transmitted to British youth at an early age while the details of French

history are not. That transmission might

possibly include reading the book itself, or extracts from it, in the

mid-teens, but more often does not.

There are simplified texts and illustrated versions for the under-tens

along with films and television series so children encounter it

repeatedly. Was that your

experience?

The

condemnation of the amatory fictions of the Alexandres Dumas, père et fils,

along with the younger Dumas’ pamphlet advocating divorce, was not due to their

‘amatory’ nature – censorship on the basis of decency was a matter primarily

for the secular authorities – but because such beguiling and exciting works

draw readers into their creators’ mindset or general outlook. That is more true of broadcast works than

written material because they are usually imbibed in a more passive manner with

less discernment on the part of the consumer.

Hence works proceeding from the dangerously flawed mentality of

undesirable types like the Alexandres Dumas should be avoided as simple

entertainments – and should be consumed only warily if at all.

The Dumas

were Bonapartists, (the father even joined the self-proclaimed emperor’s

meritocratic aristocracy) and their works were shot through with all the

attitudes and opinions that that implies.

If you had the experience I described of an early introduction to The

Three Musketeers, might I ask how much of it you believed, and how much of it

sticks in the memory? The book presents

the court of Louis XIII as having been a thoroughly decadent nest of intrigue

with a weak and ineffectual cuckold of a king, a flighty adulteress of a queen

and a scheming villain of a minister; a regime, in short, ripe for

revolutionary overthrow even then in the days of French glory. Yet these were among the greatest figures in

the history of France! Of course, there

is an implication that what had been true of one branch of the traditional

monarchy was true also of that reigning at the time of publication in the

1840s.

As was

normal under a Catholic polity, and had been the case with our own Lords

Chancellor before Henry VIII’s time, the first minister of France (the keeper

of the king’s conscience) was ordinarily a bishop made a cardinal as a mark of

papal approval of the close connection between Church and State, and with it

between secular and divine law, under such an arrangement. To depict Cardinal Richelieu as a scheming

villain amounted to an attack upon the clergy (backed up by the

characterisation of various other clerical figures across the Dumas’ oeuvre)

and not an argument but rather a certain measure of pressure in favour of

disestablishment.

The Dumas

did not promote the excesses of the Revolution but its general objectives and

its outcome as realised, in their opinion, under their supposedly imperial

hero. Similarly, in our own day, popular

historical fictions such as Dame Hilary Mantel’s (adapted for stage and small

screen) Wolf Hall Trilogy, tend not to endorse the contentious actions of their

protagonists, but by their choice of heroes and villains, their characterisation

of people real and fictitious, and their interpretation of events by which they

impose an artificial narrative arc upon carefully selected facts they make

clear where their creators’ sympathies lie and they insinuate all manner of

ideas deep into the intellectual subconscious of the consumer.

As we all

know, the imposition of an ideologically contrived narrative is not restricted

to material presented as fiction but transforms narrations of historical

events, objective facts, into effective fictions. While events as they occur certainly have a

coherence in the light of divine providence, the coinage of eternity is not

spent in a television studio packaging the past in neat and tidy parcels

congratulating today on having evolved through history into a wonderfully

enlightened present. Written history may

be flawed in many ways, but one definite advance in modern practice is that in

print the inclusion of footnotes indicating sources, and giving at least some

clue as to where facts and their interpretation can be distinguished, has

become almost universal.

It is quite

clearly possible to create historical narratives, whether of fact or fiction,

in which that which is believed to have occurred is presented in a manner

compatible with Church teaching by rejecting the Pelagian myth of constant

moral progress under the weight of human effort, or the alternative of natural

evolutionary development in the direction of freedom from antiquated moral

norms. It is also possible to create

narratives in which the ‘boo and hooray’ words and names accord with the

perspectives of faithful Catholics in wherever the narrative is set. The EWTN films we promote do exactly

that. What is not possible, however, is

a narrative that is both narrative and a neutral presentation of life as it

actually happened. ‘The past is another

country’ we do not have a visa to visit; historiography is not only possible

but obligatory if we are to achieve an understanding of history that might

allow us to build the future we want to see, but history itself is

irrecoverably impossible to grasp. The

past remains ever with us in its moral, social and political effects precisely

because we can only ever see it recreated one way or another, interpreted for us

or against.

Preciosa

in conspectu Domini. Mors sanctorum ejus

Precious in

the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints

While the media decry

the Ugandan legislation and demand retribution from the international community

and individual western nations, I can see only the blessed fruit of the life

and faithful witness in death of St. Charles Lwanga and his companions in

martyrdom by which their country has been brought to this happy liberation from

the horrors of their history.

By Prayer Crusader St Philip Howard