A Christian Essay in Aesthetic Value

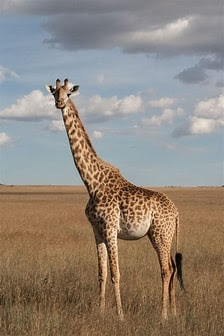

Whilst every creature represents God and communicates aspects of His essential attributes, we are alone in being made “to the image of God” (Genesis I 27, 1st lesson Holy Saturday). This entirely shapes our relationship with our fellow-creatures as their relationship with God is mediated through humanity, and our relationship with Him is determined by our relations with them. As God addresses us in them, He does not address us, His created audience, in the first instance; rather, He addresses Himself through us – he does not say “I giraffe you” but “I giraffe Myself through giraffing you” as human and giraffe are held in the heart of the Most Blessed Trinity and it goes deeper than that as the image of God in humanity brings the giraffe into the very centre of our being, our human nature. That which is in God is reflected in us, and that includes the idea from which each creature receives its nature, hence Adam knew the beasts and fowls by name as God brought them before him, and God related to them through Adam’s knowledge of them: He “brought them to Adam to see what he would call them; for whatsoever Adam called any living creature the same is its name” (Gen. II 19, Septuagesima Tues. Matins 2nd lesson). St. Robert Southwell writes:

Thus, in the fall of Adam, the entirety of the corporeal creation fell,

and all creatures are redeemed in the sacred humanity of Christ save only those

rational creatures, people and angels, who wilfully reject redemption. It was,

of course, in the fall that our ability to assimilate that which is

communicated to us through our fellow-creatures was impaired to the extent that

we are able to perceive so little in our ordinary dealings with them.

We are, however, able to relate to them, and through them to God, through our meditation upon them in the light of our ideas, our mental and moral concepts, and the powers of the soul, in which that which is in God, their creator, is reflected in us. In doing so we act in accordance with our primary vocation to participate in and to show forth the divine action, to ‘have dominion’ over other creatures by sharing in the action of the Lord. Thus, when we think about our fellow-creatures, whatever their species or nature, whether human, animal or inanimate, and whether considered in the concrete or the abstract, the particular or the generic, what we think about is our own nature, the nature of things, and the nature of the Creator of all that is. This meditation is conducted in a perfectly natural fashion by all of us as it is of our nature to act thus, even subconsciously, and when we imitate our Creator in this way, we find in ourselves the echo of this action as, in John Crowe Ransom’s words, “out of so simple a thing as respect for the physical earth and its teeming life comes a primary joy, which is an inexhaustible source of arts and religions and philosophies”. As we see that the created order is very good, goodness begets in us the desire to communicate goodness (which is, theologically speaking, a motion of grace, the action of the Holy Ghost), and so the artistic impulse is born; and in the image of the Creator we create, not, as He does, ex nihilo but from His creation and the image of it He created in us. In the practice of the arts we take possession of the world, and we take possession of ourselves, of the image of the divine that constitutes us as human. In his ‘Letter to Artists’ St. John Paul II tells us that “Every genuine art form in its own way is a path to the inmost reality of man and of the world. It is, therefore, a wholly valid approach to the realm of faith, which gives human experience its ultimate meaning.”

To understand the arts in this light is to grasp a sense of purpose from which a scale of aesthetic values may be extrapolated; and that enables us to pass an objective judgement, giving a context to the subjective reactions we feel when confronted with the artistic endeavours of others. Art may be good or bad, it may succeed or fail in its own terms, precisely as art. I ought, perhaps, to mention at this point that 2013’s Reith lectures were on the subject of art and were delivered by Grayson Perry, but this essay-article is neither a commentary upon nor a response to his talks, which are worth reading if you did not listen to them. The only comment I will make is that he was dealing with the visual arts whilst I am discussing the arts in general, and that much of what he has to say is really concerned with comparatively superficial questions of public attitudes towards art and artists rather than the philosophical and theological issues under consideration here.

To be continued...

By Prayer Crusader St Philip Howard

No comments:

Post a Comment